Painted Poems, Written Images

Poetic Art by Ōtagaki Rengetsu

The special exhibition "Painted Poems, Written Images – Poetic Art by Ōtagaki Rengetsu" brings together paintings, calligraphy, and ceramics by Japan’s most famous 19th-century female artist. Her reputation stems not only from her skills as a poet and ceramist but also from her unique artistic concept of combining poetry, calligraphy, and pottery. In Rengetsu's work, different genres merge into a total work of art, creating a unique style called Rengetsu-yaki, or Rengetsu ware. From Rengetsu’s hand, we find mainly calligraphic works with either with or without painted images and small, hand-shaped ceramic vessels such as teapots and bowls, sake bottles and cups, flower vases, trays, etc., all of which are inscribed, painted or incised with her poems in her elegant and fluent handwriting. Despite the purely aesthetic appeal of her art, Rengetsu often reveals a sophisticated and complex relationship between materiality and meaning in her works.

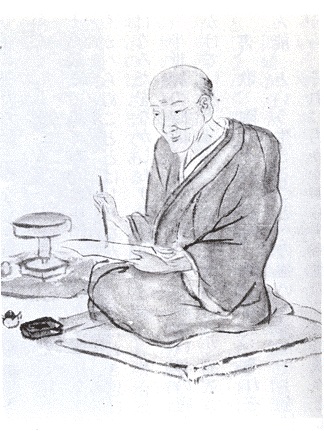

Rengetsu's Life

Rengetsu was born the illegitimate daughter of a courtesan and a high-ranking member of the Tōdō clan of Iga Province. She was adopted as an infant by the low-ranking vassal Ōtagaki Teruhisa, who was appointed administrator of the Buddhist temple Chion-in in Kyōto that same year. Until the age of eight, Rengetsu was raised in the religious atmosphere of the Jōdo temple. She received instructions in literature, classical arts, and martial arts from an early age. In 1798, Rengetsu was send to the household of Kameoka Castle, where she worked as a chambermaid and received an education befitting the noble status of her biological father. Her education included calligraphy, tea ceremony, flower arrangement, dancing, and others. In martial arts, for example, she even reached the level of a teacher, which she maintained throughout her life. The year 1803 was overshadowed by the sudden death of her stepbrother and her stepmother and she returned to the Chion-in, where she married an adopted son of the Ōtagaki family in 1807. Her three children born between 1808 and 1815, all died young, causing an emotional crisis that led to the separation from her husband in the summer of 1815.

"A pure name

flows throughout the world

incomparable

as the Japanese spirit and

water flowing under chrysanthemums."

In 1819, Rengetsu married a second time to another adopted son of the Ōtagaki family and gave birth to a daughter. However, the daughter did not survive, and also her husband passed away from illness. It is said that Rengetsu promised her beloved husband on his deathbed to shave her head and take the vows. Immediately after her husband's death in 1823, Rengetsu became a nun with the Buddhist name "Lotus Moon" (Rengetsu) at Chion-in, where she lived in seclusion with her stepfather until his death in 1832. The loss of her stepfather, the last known family member and the only father she had ever known, hit her hard at the age of 42, leaving Rengetsu to fend for herself. Rengetsu was proficient in certain martial arts and the abstract strategy game Go, but as a woman, the prospect of teaching in these male-dominated fields was unlikely.

Without a family and free from official temple obligations, she settled in the Okazaki district of Kyōto, a popular area for artists. She studied classical Japanese waka poetry with Kagawa Kageki (1768-1843) and Mutobe Yoshika (1798-1864) and within only a few years she gained a reputation as a poet that led to her name being listed for the first time in the 1838 Heian jinbutsushi (the “Who's Who of Kyōto”) (as well as in later editions in 1852 and 1867). Around this time, Rengetsu began to combine her poems, written in slender, graceful calligraphy, with her own paintings, and began to make utilitarian ceramics for subsistence. She worked as a self-taught potter, and her simple, hand-formed vessels decorated with her own poems stood out from the traditional, material-rich Kyōto pottery (Kyō-yaki) and successfully filled a gap in the market. Her reputation as a poet and her separate, unusual independence as a nun and professional artist in a traditionally male-dominated arts and crafts industry contributed to this.

In the last years of her life, Rengetsu deepened her Buddhist studies and continued to be artistically active. In 1865 she settles permanently in a tea hut at the Shingon temple of Jinkō-in, where she was ordained a nun under the abbot and former professional painter Wada Gozan (aka Gesshin., 1800-1870) with whom she had a close and productive artistic collaboration. Rengetsu died of typhoid fever and was buried in the neighboring Saihō-ji temple. The epitaph for her grave stone was made by long-term friend and protégé Tomioka Tessai (1837-1924).

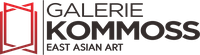

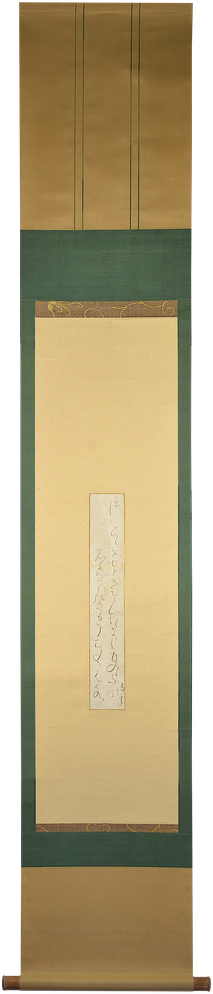

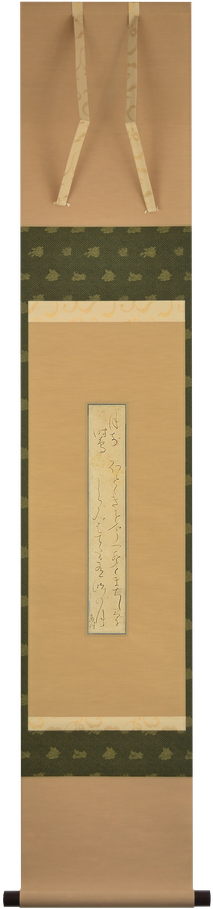

Four Tanzaku mounted as Hanging Scrolls

Moon at the Riverside

"My eyes float past

the reaching and pulling

on a riverboat...

Walking with the moon

in Hirakata village"

Famous Place at the River

"Here in the shallows,

warriors vied to cross

their names carried

to fame and oblivion

on the waters of the Uji."

Little Cuckoo in Front of the Moon

"A little cuckoo,

while awaiting

one more chirp

it has faded out completely—

the morning moon."

In Praise of the Pines

"Yearly refreshing their youth...

How long has she

lived in this world?

Princess pine

on the shore of Suminoe."

"Fluttering

in a field of flowers and dew

now dozing away...

In whose dream

is this butterfly?"

Rengetsu'S Work

Rengetsu’s reputation is derived from her skills as a poet and ceramist, and her unique artistic concept of combining poetry, calligraphy and pottery. In Rengetsu's oeuvre, different genres merge into a total work of art, which has generated a name of its own that refers to both her work and her style in general. The so called Rengetsu-yaki, or “Rengetsu ware,” became its own brand influencing many friends, colleagues, and other artists during her lifetime, who began to produce and reproduce her work far beyond her death. From Rengetsu’s hand are mainly preserved small-format vessels like teapots and bowls, sake flasks and cups, flower vases, trays and so on, all inscribed, painted or incised with her poems in her elegant and fluent handwriting.

Living in the Okazaki district of Kyōto for a number of years, Rengetsu was surrounded by the intellectual and artistic elite of her time, who favored the art of brewing Japanese steamed tea (sencha) in the Chinese manner. Thus, especially in her early artistic years, starting in Rengetsu's 50s, she created many objects for drinking sencha. Her early surviving ceramics are very delicate, hand-formed tea utensils bearing her calligraphically incised or pictorially applied poems under rice straw or ash glazes. One such example is the sencha teacup with wild goose poem and painting, which is an epitome of her style.

"Dark clouds

across the moon,

unwelcome,

until I hear their cries –

a sky full of wild geese."

The bell-shaped cup with very thin walls is made of cheap clay, and the impurities in the cup's glaze are the result of simple firing. The overall shape is distorted but well balanced. The surface is covered with rice-straw-ash glaze, inscribed with a poem in iron oxide brown, thin brush lines, and is decorated with three painted birds. Rengetsu’s characteristic style of calligraphy is fluid, showing a subtle line management of clearly separated and easily readable, but elegantly linked characters, whose overall arrangement is perfectly placed as an almost gauze-like cover on the clay ground of this tiny cup. As we can see in this example, Rengetsu’s poems were written predominantly in the Japanese kana syllabic writing system, with only few Chinese characters, and were thus accessible to large segments of the population.

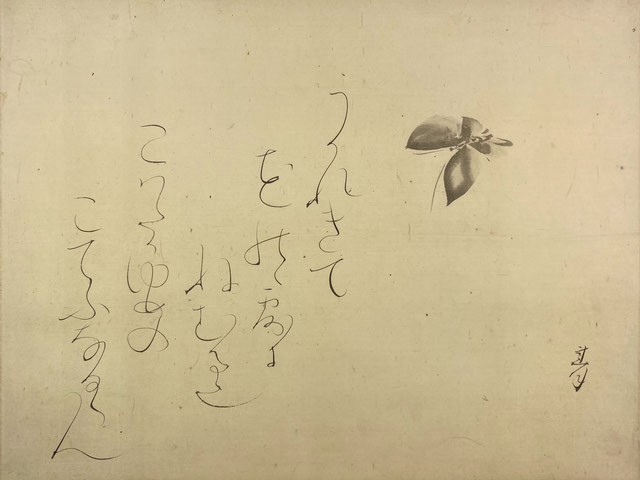

Transscription of the POem from Right to left

In her poem, Rengetsu describes a scene of a darkening sky, which at first seems threatening and unpleasant, until the moment when the voices of wild geese are heard. On the surface of the teacup, she combines her poem with the image of three wild geese in her abbreviated brushstrokes. It is often said that in most of Rengetsu's paintings, the painted images function simply as a accompanying illustrations to visually support the content of her calligraphic poems. But not so here.

While the wild geese in the poem are hidden by the clouds of the darkening sky, two of them appear on the cup just between the lines of the written poem. Rengetsu placed them just below and behind the character for sky, ten 天, which is written and read here as amatsu 天つ, meaning “in the sky”. As if the readable and only indirectly intellectually accessible text were a cloud that hides the natural, direct inner experience, the text is pushed away to free the view on the acoustic source named in the poem. Rengetsu not only combines text and image, but plays with the visible and the invisible itself. The cup therefor works as an anchor to link the immaterial imagination of the cackling geese, forced by the poetic inscription, with the material, haptic and sensual impression of holding, turning and viewing the teacup in one’s own hands. What at first appears to be a simple work of art reveals many layers of meaning, making this tiny cup a highly complex masterpiece

"To rise in the world

and achieve

what one desires,

therefore, eggplants are indeed

a fortunate example."

Artistic Collaborations

To meet the high demand for her ceramics, Rengetsu collaborated with potter friends (especially Issō and Kuroda Koryō). In the beginning, the professional potters made the clay body into which Rengetsu incised her poems or applied them with a brush as an underglaze inscription. Later, with or without Rengetsu’s official approval, these potters started to independently produce their own Rengetsu-yaki with their own inscriptions in Rengetsu’s calligraphic style. Kuroda Koryō, for example, even became her descendant as Rengetsu II. But also friendly potters such as Takahashi Dōhachi III (1811-1879), who worked in the Kiyomizu area of Kyōto, known for its colorful and richly decorated ceramics, began to work with Renegtsu or in her style, which was in sharp contrast to his own. The flower vase with two handles and Rengetsu’s autumn poem may be his work. The poem is signed with “Rengetsu” but is not by her hand, so it is not really a signature but rather a token of appreciation and a label to show that the poem was composed by her.

Probably in the 1840s, Rengetsu studied painting of the Shijō school with Matsumura Keibun (1779-1843), which was followed by the acquaintance and artistic collaboration with numerous (Shijō) painters, such as Yokoyama Seiki (1792-1864), Mori Kansai (1814-1894), and Kishi Chikudō (1826-1897), but also Tomioka Tessai, 1837-1924, Takabatake Shikibu, 1785-1881 (Rengetsu Shikibu nijo waka shū, “Collection of Poems by the Two Women Rengetsu and Shikibu”, published in 1868) and personalities including the Tendai priests Rakei Jihon and Gankai or for instance the Zen monk Hara Tanzan, all of whom were part of Rengetsu’s wide network.

In 1847, Rengetu was mentioned in the Kōto shoga jinmeiroku, “Catalogue of Calligraphers and Painters in the Imperial Capital,” for her talents in various art categories: waka poetry, calligraphy, painting, and pottery. Her frequent moves together with her protégé, the youthful Tessai, beginning in 1856 (including to the grounds of Hōkō-ji and Shinjō-ji temples and to Nishigamo) led her to her final permanent settlement in a tea hut at the Shingon temple of Jinkō-in in 1865, where she was ordained a nun under the abbot and former professional painter Wada Gozan (aka Gesshin, 1800-1870). Rengetsu spend the last years of her life in Buddhist studies, but continued to be very active artistically. She had a close and fruitful artistic relationship with Gozan and produced, for example, over 1000 paintings depicting Kannon Bosastu (Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara).

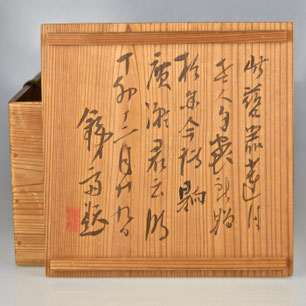

For her pottery, Rengetsu collaborated not only for a faster, more efficient production, but also to show her close ties with some of the most famous artists and craftsmen of her time. One such an important collaboration is the fantastic lidded freshwater jar with poem and painting of chrysanthemums. The container was created by a total of three artists who shared their artistic creativity to bring this masterpiece to life. The famous Kyōto potter Kiyomizu Rokubei III (1820-1883) has shaped and glazed the pot. Unlike the fine, elaborate Kyōto ware, he used a coarse, less cleaned clay with a rough texture and a thick, milky white, crackling rice-ash glaze that he poured freely over the clay body.

On the flat lid, he attached a handle made of a crude piece of clay and pressed it to the ground with his bare fingers, not caring to smooth its contours. Rengetsu then wrote her poem on the flat surface of the lid, starting at the top right in vertical lines from right to left. She added her signature on the lower right part with her age of 75, dating the piece to 1866/67. In contrast to her poetic inscription, her signature follows the round curve of the lid’s rim, and the entire composition is held together by a single circular line painted as a frame with the same brush and glaze. Her poem reads:

"In the palms of my hands

waiting for eons to pass…

I hear drinking this

will make me younger—

the chrysanthemums’ hanging dew."

Around the vessel's wall, Rengetsu's protégé and soon-to-be greatest literati artist of Japan, Tomioka Tessai (1837-1924), painted a few chrysanthemum flowers in his own free and spontaneous way, using abbreviated brushstrokes. He was only 30 years old when the three artists worked together to combine four very different media in a single work of art: pottery, painting, poetry, and calligraphy.

Supported by Tessai’s painting, Rengetsu’s poem suggests that the water contained in the jar was not just simple water but morning dew collected from chrysanthemums blossoms. Despite the Buddhist implications of dewdrops reflecting the ephemeral world, a more Daoist interpretation comes into play here: In Daoism, the meaningful symbol was believed to be an elixir of eternal youth and health, granting immortal life. Already the Zhuangzi (c. 4th century B.C.) describes the Daoist sages as spiritualized beings who dwell far from the turbulent world of men, dining on air and sipping dew.

With these implications, the bare materiality of the jar adds another layer of meaning. The sandy clay and the crackling glaze are not usually the best materials for a jar that is supposed to hold water. Here, however, the intention seems to be that the water inside the jar will slowly evaporate through the porous material. As a result, after a while, small drops of water appear on the vessel’s wall just on the surface of the painted chrysanthemums, giving the impression of the vitalizing hanging dew of Daoist legend.